Home | City Notes | Restaurant Guide | Galleries | Site Map | Search | Contact

It is kiss-me-now spring

but the wind blows cold and no one is kissing me now. Waking in a fever

from a dream, I get up and go through the City ...

I am making the rounds. Le Central, B44, Enrico's. It is cool now but no longer icy cold. The wind is no longer shoving you down the street, just gently pressuring you to keep moving. A Kettle One martini at Central provides some internal heat, a Woodford Reserve bourbon at B44 more, and now an Old-Fashioned at Enrico's Sidewalk Cafe completes the job; I am warm toast just out of the toaster. I have been assigned to cover the bars in San Francisco for a week—yes, I'm the "booze editor"—and in the City this is a serious assignment. It also gives you the right to drink during the day. Salud!

The calendar says it is spring but no one here in the City believes it. Not when your hands are so cold you are thinking about making a trip to Macy's for gloves.

Now, however, it is not so bad. I am sitting at a table at Enrico's in the middle of the day watching passerbys. Dorrell has just brought the Old-Fashioned.

Back at B44 I had food with my bourbon—Brandada. Know that dish? It is a real challenge to any restaurant. It is made of salt cod, mashed potatoes, garlic, olive oil .... Now B44 is a fine restaurant, and if this is the worst thing on the menu, they are doing very well indeed. It is hard to imagine how such a dish could taste like much—mashed potatoes and cod?—and experience proves that to be so. The dish is a challenge. Cafe Claude also offers a version of it, but so far I have stayed clear of it.

Usually when you go to a restaurant you try to order the best thing on the menu or your favorite dish. Then you judge the restaurant. That is a sane thing to do. But there is another approach to judging restaurant quality. Order what you think might be the worst. Ask the waiter about an item—go down the list—and if he or she makes a face that says, in effect, "better stay away from that one," order it. You will then know the restaurant at its worst. The experience will be enlightening, though a bit of a downer.

At B44, Anna, the bartender, had made that face at me, and I immediately said, "That's what I'll have."

At

Enrico's I did the opposite. I ordered Orecchiette paste, "house-made,"

with mussels, and it was quite delicious. The pasta was puffy and moist,

as fresh pasta usually is, and it came topped with shredded basil. Not

to be beat. So what is the worst at Enrico's? Nothing on the menus looked

bad, so I guess I will never know.

At

Enrico's I did the opposite. I ordered Orecchiette paste, "house-made,"

with mussels, and it was quite delicious. The pasta was puffy and moist,

as fresh pasta usually is, and it came topped with shredded basil. Not

to be beat. So what is the worst at Enrico's? Nothing on the menus looked

bad, so I guess I will never know.

It was April now and I wondered where the good weather was. It was the time of pilgrimages in Old England, a time when the "smale fowles maken melodye" and sleep all night long with open "ye." Where were the kisses, the sly, inviting looks, the green grass, the clover? All there seemed to be was a blast of cold wind, like a slap in the face, and a harried look in women's eyes.

My eyes began to rove the street for friendly sights. There is the Black Cat directly opposite Enrico's, Fuse on the opposite corner; above Fuse the massage place for "Men & Women," with an outcall number. Each place has its own color or colors. The Black Cat is red and black; Fuse is blue; the massage place is chipped and faded gray. Next to Fuse and down the street is a sex amusement center, which seems to mostly draw teenage males; further down the street is the Crowbar, once Basis Street West, and now a more-or-less redneck bar with pool tables; then there is Centerfolds, a strip-joint with mostly college-girl strippers. If you have not guessed it, the establishments on Lower Broadway are not necessarily "nice" but they are rich—they have a colorful history too—and I will take rich over nice any day of the week.

On the other side of the street and up towards Columbus is the Garden of Eden, Little Joe's restaurant with the big grill, and Little Joe's bar with the TVs and a game always in progress ...

And if you look up from all this in the direction where Kearny comes up the hill to Broadway—okay, you may not want to do this—you will see the financial district in the background with the Transamerica pyramid gouging its way into the skyline. If you do look, you will be awed by the sheer weight of the buildings of the financial district—all that crushing mass of concrete—and then you will be amazed how North Beach and Lower Broadway—all low, wood-brick structures—hold their own against all this. It is David versus Goliath, with David still winning. Or heart versus mind and machine. The shack is still homier than the stone castle.

Now up the sidewalk comes a man clutching what looks like a ledger book—it is tax time and he looks worried—then comes some French tourists with map in hand and children in tow ("Pierre, Catrine ..." calls the mother urging them to keep up), then some Chinese women with plastic bags crammed with produce, then a hippie guy wearing a beret and dressed in a red-silk pants that give him a clown-like appearance. Then a young woman, braless and bouncing, her hair still wet from washing, stops, asks if I have a cigaret (I don't), smiles a faint "Thanks, anyway," then saunters on down the street. The scene goes on. Some of the characters you would see anywhere, others are indigenous to North Beach.

"But so what?" you say.

Okay, so what? And so what if the wind blows and it is cold, and when it would be spring it is not? And so what if Miles Davis' opening tune on Kind of Blue is called "So What," and has a wearisome though wise feeling to it? I guess I will get used to that bluesy feeling and find what I find, okay? Come, let us take a walk and pursue this together.

Dorrell is wearing a leather jacket

when he comes back out with olive oil and bread. He says business has been

down. But the good news is that the cause is not "9/11"; it's the

wind. Praise the lord, praise mother nature!

How beautiful you are my love, how beautiful you are. You eyes are doves behind your veil, your hair is like a flock of goats surging down Mount Gilead.

It is about 1:30 in the afternoon, and the mayor is at the end of the bar at Le Central on Bush Street. He is alone having a drink. Toni, the bartender, comes by and asks him if he is going to have lunch.

"Haven't decided yet," says the major and takes another sip of his drink, Belvedere Vodka in a wine glass with ice and a splash of OJ, I believe.

"Usually the stomach has made a decision by the end of the first drink," I say.

"Not necessarily," says the mayor. "Sometimes mine says, 'have another drink.'"

I ask him how he handles all the banquets he attends.

"I don't touch anything," he says. He tells me that he tries to "eat healthy," which surprises me a little. I had thought of the major more as gourmand than health nut. And when it comes to drinking, he says he just has a little champagne in a glass filled with ice. I am curious because, as booze editor, I have a similar problem to that of the major's: drinking on the job while getting the job done and not bringing shame on your employer. Think it sounds easy? Give it a try!

He tells the story of a woman he

was once talking to in a bar downtown. "She had about three black Russians," he says, "then she fell right off the back

of her barstool onto the floor."

three black Russians," he says, "then she fell right off the back

of her barstool onto the floor."

The mayor says he was about to jump up and administer first aid, as were several nearby customers. But the woman got right back up and sat on the barstool and continued the conversation as if nothing had happened.

"You should have hired her on the spot," I say. "With poise like that you could use her."

The mayor only smiled faintly at my suggestion. I think he has learned to discipline his tongue since the beginning of his first term in office.

He says they continued their conversation for another fifteen minutes or so, then the woman got up, walked a straight line to the double doors of the bar-saloon and left.

"I expected to hear a crash when she got outside," he says, but it didn't happen. He says he has never seen her since.

I am having a martini on an empty stomach and feel a little woozy. Nevertheless, I have an appointment down the street and excuse myself. I make a pretty-straight line for the door and there is no crash outside despite a wind that would flatten you.

Your lips are a scarlet thread

and your words enchanting; your cheeks, behind your veil, are halves of pomegranate.

I am always looking for restaurants with long hours, and Nicole, bartender at Redwood Park in the Transamerica building, mentions Globe down on Pacific. I have never heard of it. Nicole also knows the Sazerac, that New Orleans cocktail that is popular on the East Coast but practically unknown out here. As part of my job as booze editor, I have been keeping tabs on which bars in San Francisco know the Sazerac and which don't. Every job involves statistics, so these are mine. If anyone asks for hard figures on anything, I cite stats on the Sazerac and they move on to another topic. It is my own little unfriendly wind that moves a conversation along. I order Duck Fat Fries, which come in a white-paper cone, and we disagree over who the singer is on the CD being piped throughout the restaurant. Nicole says it is someone name Brian; I say it is Steve Tyrell. Whoever it is, he is not very good. Know Steve Tyrell? He takes everything Sinatra ever did and degrades it. He is an emotional gusher in the style of Billy Joel. Simply put, he sounds like he is becoming unglued. His voice cracks and he gushes emotions that are manufactured, not felt. The arrangements are as bad. This is not the Nelson Riddle orchestra backing up Frank Sinatra but a cheap pickup band with sketchy arrangements. The Duck Fat Fries, however, are authentically good, and I put Globe on my list of places to visit.

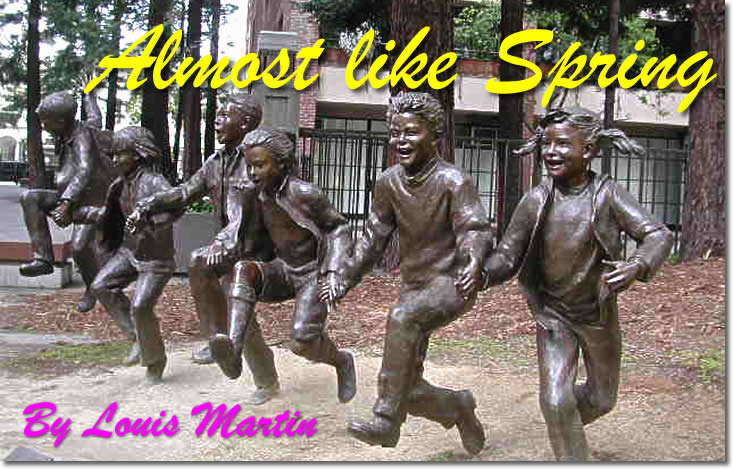

As Nicole carries drinks over to a couple by the window, I finally spot the redwood trees and the park outside—this is my first visit here—and now the name, Redwood Park, suddenly clicks for me. There is a very well tended park outside the building with redwoods, fountains, flower gardens, and sculpture, the most striking piece being "Puddle Jumpers" by Glenna Goodacre. Now there, maybe, is a bit of the spring I have been looking for. What could be more spring-like than these puddle jumpers, all young children holding hands and in their own private world of joy as they lift their legs to jump over an imaginary puddle? This is not the gush of emotion of singers trying to make it to the top of the charts; this is the "Infant Joy" world of William Blake.

Your two breast are two

fawns, twins of a gazelle, that feed among the lilies. You are wholly

beautiful my love, without blemish.

The next day I wander down to Globe, which is located on Pacific, deep down in the Jackson Square area, between Battery and Front. This is the area of historical old San Francisco that made it through the '06 quake intact. Most of the buildings are two-story brick structures that were reinforced years ago, with bolts and square metal plates on the outside, to withstand earthquakes. This is the area in which the young Mark Twain worked as a reporter during a period of high seismic activity during the 1860s and about which he wrote that it "rained bricks."

The bar at Globe is open all day up to 1 AM, and food is served all but from 4 to 5:30 in the afternoon. It is single-story brick structure with youthfull-looking customers; compared to the surrounding financial area establishments, it is "hippyish," though not hip (too young, too much money).

Next door is The Old Ship Saloon, again a single-story brick structure that on the outside really looks like an old San Francisco saloon. The reason? Fancy renovation? Clever redesign? Digital holography? No, it is one of the historical San Francisco saloons (1851). It was also once a brothel. On the inside, however, it is a product of much renovation. There you would think you were in an upscale yuppie bar used for a TV sitcom. Says Johnny, the bartender, "Most order light beer or white wine." Johnny looks like he would really like to pour hard booze, and he seems pleased when I order a Manhattan. He says he used to work at Harrington's Bar & Grill but is "much happier here." It is a little hard to believe that, but only Johnny knows how Johnny feels.

The

Old Ship Saloon is spacious inside with the bar not against a wall but

in the middle, exposed and open. Somehow I picture Johnny more comfortable

with the bar against the wall. The interior wood is pale as a Bud Lite,

and there are two TVs located high on the walls, the volume of each turned

discretely low. In the back are tables where peer groups of the predominantly

young customers sit. All look like they work in small offices in the surrounding

areas of Jackson Square. This is a different crowd from the financial

district, which is largely lawyers and accounts. Here we seem to have

architects, designers perhaps, and more artistic but well-heeled types.

The

Old Ship Saloon is spacious inside with the bar not against a wall but

in the middle, exposed and open. Somehow I picture Johnny more comfortable

with the bar against the wall. The interior wood is pale as a Bud Lite,

and there are two TVs located high on the walls, the volume of each turned

discretely low. In the back are tables where peer groups of the predominantly

young customers sit. All look like they work in small offices in the surrounding

areas of Jackson Square. This is a different crowd from the financial

district, which is largely lawyers and accounts. Here we seem to have

architects, designers perhaps, and more artistic but well-heeled types.

Johnny looks hell-bent on being adaptable, but he looks like the one item that does not fit in this place. He looks like a bar stool that is shorter or taller than the others, a chair with the wrong finish or a gouge in it, or an ash try with a cigar butt. His voice is harsh, almost choking. He has to force his voice to make the words come out, and they come out with a rasping sound. He makes me one hell-of-a strong Manhattan, however; and I drink only part of it, following the mayor's rule, and depart. I head for North Beach and the Crowbar. I like Johnny but he looks like he belongs with the old 1850s saloon or brothel, and I don't spring is to be found at the Saloon, either the current one or the one of the 1850s.

How delicious is your love, more delicious than wine. How fragrant your

perfumes, more fragrant than all spices.

I have only met Sage once before but she calls me by name and remembers my drink. Nothing like having a young woman say your name and reach for a bottle, unless, of course, it's the wrong bottle. She is tending bar at the Crowbar on Lower Broadway in North Beach. Sage has a quietness about her and amused, thoughtful eyes. The first time I came in, the big bar was entirely empty and she was standing at the end of the bar writing in a journal.

"Writing a book?" I asked.

"No," she said, looking a little embarrassed and closing the journal.

Now an older guy comes in and orders a beer, and the three of us fall into a conversation—an interesting one, as we span several generations—about taxes and war. The older guy is an ex-marine. He takes a broad interest in the world but says he is surprised that some people, his wife for one, take no interest at all. The other days, he say, he discovered that his wife had never heard of the Cherynobl nuclear accident. He does not say this in a critical way, just as a curious fact.

We talk about "9/11" and the continuous replay of the jetliners hitting the World Trade Center in New York. All talk all day long at the Crowbar was about the attack, says Sage. When she got home and her friends were watching the news on TV, she says she watched for awhile, then said, "let's turn if off." I did the same thing. The effect was eerie. It was like being in a vacuum.

"But the strange thing was," says Sage, "that a woman came into the bar—one of the strippers from Centerfolds—and she had heard nothing about it." Too much stripping I thought later? Or not enough wearing of clothes and watching the tube? Some imbalance there anyway.

The older guy leaves and Sage tells me she has applied to San Francisco State University for the Masters program in creative writing but doesn't know if she has gotten in yet. Her father is going in for heart surgery and would like some "good news", she says.

"Why don't you just tell him you got accepted," I suggest.

She gives me a funny look.

"When he's all well, you can tell him there was some kind of mistake," I say. She is amused at the idea and lightens up.

I ask her if she has ever made a Caiprinha. She says no. I get out the bartending guide that I have been carrying around with me on my "assignment" and she looks over the recipe. I tell her I have just had one very good one down at B44 and one very bad one at a bar I will not name, as I want to continue to feel welcome there.

"The trick," I tell her, "at least according to Tim Staeling at B44, is the balance of lime and rum." The bad one I had was made with excessive amounts of lime, overwhelming the flavor of the rum. The drink calls for cachaca, a Brazilian rum made not from molasses, as most run is, but sugar. It has a lighter, more delicate flavor than most other rums and a sweet, honey-like smell. Add too much lime or squeeze the lime wedges too much, and you might as well add vodka or gin. You ain't gonna taste the cachaca.

Now as it turns out, Sage does

not have cachaca on hand but she does have Captain  Morgan's

spiced rum, and she thinks she can make something like a Caiprinha.

Morgan's

spiced rum, and she thinks she can make something like a Caiprinha.

"Want me to give it a try?" she asks.

I am doubtful but give her the go-ahead, meaning I will pay for it. She starts mixing, and she is very careful of the amount of lime. She puts about six wedges, unsqueezed, into a Collins glass and adds the sugar and the rum. I am not expecting much, but it turns out to be quite good. The spiciness of the Captain Morgan's rum cuts through the lime nicely, producing a very pleasing taste and smell. It is as good, maybe better, than the one at B44, though not quite the same thing.

"Well, if you don't get into graduate school, you can always ..."

She doesn't look happy with the idea.

"Could be worse," I say. "As a bartender at least you are talking with people."

"Not all customers are that interesting to talk with," she says.

Just then some rowdy young guys come into the bar, baseball caps on backwards. They look like they have just gotten off from a construction project and reversed the direction of their caps. Sage starts pouring beer and shots. Their laughter, which is not all that friendly, fills the space that once was filled with the music of such jazz greats as Dizzy Gillespie and Hampton Hawes.

I hear my exit cue and go.

Your two breasts are two fawns,

twins of a gazelle, that feed among the lilies.

Sunday is my excuse for going into the "Hungry i" in North Beach. She is always a bit of Spring to me. She works bar there a couple of nights a week, and otherwise studies music, paints, and makes clothes. She is a small Asian bundle of mirth and charm. She has a sister named Beautiful and a brother named Casanova, which always leaves me wondering about the romantic state of mind of her parents when they conceived these children.

But what interested me this night at the Hungry i was not Sunday, or so much Sunday, but a young student from Spain. Dark-haired, fair-skinned, rouge-lipped, and dressed in funereal black, she sidled over to the bar and asked me how I was doing, or some such thing, to start a conversation. She was new at the Hungry i and looked a little hesitant. All the new girls are hesitant until they get the hang of it. They are learning to make what is called a "cold call" by sales personnel. Usually sales person and what is being sold, the "product," are two different things. Here, of course, the product does the talking.

Selina was her name, and what first interested my about her was the accent. She was a foreign student. But I'm even more interested when she tells me she is from Madrid and that she is studying mortuary science at the San Francisco School of Mortuary Science. In fact, she is in the last graduating class at the school located out in the Mission district conveniently near Reilly Company, Goodwin & Scannell, "one of San Francisco's most historic funeral homes," according to the school's web site. Translation: lots of dead bodies. But apparently lots of dead bodies doesn't make it these days for a mortuary school. Selina is from the last graduating class because the school is closing. The reason? The school says it's because of the high cost of living in San Francisco. And also because the landlord is destroying the building and the school doesn't want to relocate in the City.

Selina comes from a family of morticians and has decided to go into the family business. There is good money in the business, she says.

Comparing the business to that of selling automobiles, she says, "People have to buy but they don't have much time." When buying a car, people do have the time to shop around and compare. But when a loved one dies people are not in the mood to go bargain hunting; moreover, there are not many choice of mortuaries in a given locale. Hence, the money is good and it is not that competitive.

She tells me she is up on stage next and has to go. "I'll be back," she says. We shake hands, and I apologize for my cold hands. The winds, as usual, are blowing cold on the street, and I have just walked down from Nob Hill.

"I'm used to that," she says with amusement.

She

is dressed vampire-like. I don't usually watch the girls dance; I talk

with Sunday. But when she comes on stage I watch for awhile. I notice

that she does not remove any clothes anytime soon. In fact, at the end

of the dance, she is still almost fully dressed, except that she has unzipped

her top, so that her breasts, the nipples covered by large silver stars,

are bare. Each girl at the Hungry i has her own style. Danae is warmhearted

and just lets it all hand out; one girl likes to the climb the pole on

the stage upside down, letting her breast hang the opposite direction

from usual, towards her head; another plays the blond sex kitten, and

is such in real life too, for all I can tell. For most it is a persona;

it is an acting out. Now we have something new, something Spanish in style:

a bolero, a fandago, a farruca? I'm not sure but there is something Spanish

and traditional about it. And the silver stars, which give off little

flashes of light, are more dignified than the the bear nipples of the

upside down girl on the pole. Selina is a welcome addition to the Hungry

i.

She

is dressed vampire-like. I don't usually watch the girls dance; I talk

with Sunday. But when she comes on stage I watch for awhile. I notice

that she does not remove any clothes anytime soon. In fact, at the end

of the dance, she is still almost fully dressed, except that she has unzipped

her top, so that her breasts, the nipples covered by large silver stars,

are bare. Each girl at the Hungry i has her own style. Danae is warmhearted

and just lets it all hand out; one girl likes to the climb the pole on

the stage upside down, letting her breast hang the opposite direction

from usual, towards her head; another plays the blond sex kitten, and

is such in real life too, for all I can tell. For most it is a persona;

it is an acting out. Now we have something new, something Spanish in style:

a bolero, a fandago, a farruca? I'm not sure but there is something Spanish

and traditional about it. And the silver stars, which give off little

flashes of light, are more dignified than the the bear nipples of the

upside down girl on the pole. Selina is a welcome addition to the Hungry

i.

I ask Sunday if it seems like Spring. "No, too much wind," she says. But she says that is good for her clothing business. "It delays the shopping season," she says, and that is a good thing because her clothes are not ready for market yet. It is pleasing to know that this ill weather is profiting at least someone.

Later, two young women come in and sit down at the bar to the right of me. They look out of place but I don't know why. Police? I don't think so. I turn to the young woman on my immediate right and say something about the remodeling of the bar. The Hungy i is being remodeled during the day when it is closed for business. She says she doesn't know anything about it and glares at me with sharp, critical eyes. She is carefully and fully dressed—not one bit of bare skin shows except on face and hands—and I'm sure she is not a dancer trying to impersonate a country school teacher. I ask her what brought her in.

"We're making a documentary about the dot-com effect on the sex industry," she says. I don't quite know how they are planning to do it, since no one is talking to them other than me. I tell her that most of the women that work the business on Lower Broadway are college students, which I have learned from many hours of talking to women who work on Lower Broadway. She says this is not true. I suggest that the "demise of the dot comers," a topic nearly exhausted now, has about the same effect you would have with any other economic downturn. People don't spend money they don't have. Again I am wrong.

"The customers used to be young people with money," she says, emphasizing "young."

I look around and see nothing but young people. But I say nothing.

I'm used to being wrong. "Better lucky than right," my father used to say. If you look at it that way, wrong is not bad at all. At least you are alive, the bullet missed, the car didn't go off the cliff ... I give up talking to her and wonder how they are planning to get any real information for their documentary, let along shoot a video for it. First they will have to quit looking like WCTU members.

Your lips, my promised bride,

distill wild honey. Honey and milk are under your tongue; and the scent

of your garments is like Lebanon.

At this point I was ready to get out of town. The flowers were surely in bloom in Mendocino, so I headed for a friend's ranch near the town of Elk. Driving through Andersen Valley towards the coast, I see that Mendocino is very green now, and I see poppies on the sides of the road and yellow mustard and lupine. Up on Greenwood-Philo Road I see sheep in the lush green grass of the apple orchards. Nothing is as idyllic and as spring-like as that. Nature's spring was happening out in the country, even if my own mental state was more like winter.

Later, settled in for the evening

on the ranch, I hear a motorcycle coming down the hill. It is my old friend Ramon, who has come down to feed his mules, which he pastures

in one of the meadows. He stops by for a minute to talk and spends an

hour. I have writing to do but put it aside. Ramon always finds the time

to stop and talk with people, and it would be a sacrilege for me to do

otherwise. Ramon's beard has grown over the winter and he is wearing about

three shirts and a heavy jacket. He

is so well padded he looks like he could dump the bike without a scratch.

my old friend Ramon, who has come down to feed his mules, which he pastures

in one of the meadows. He stops by for a minute to talk and spends an

hour. I have writing to do but put it aside. Ramon always finds the time

to stop and talk with people, and it would be a sacrilege for me to do

otherwise. Ramon's beard has grown over the winter and he is wearing about

three shirts and a heavy jacket. He

is so well padded he looks like he could dump the bike without a scratch.

Ramon lives in a barn up on the Sankula Ranch. He is a logger and a tree trimmer with a reputation for careful and expert work. He loves the woods and you can hear it in every word he says. He is also a guy who "always has the time"—and not because he has nothing else to do. He is not an idler, either physically or mentally, and in conversation he always moves into the vital part of it.

Ramon has a violent and amorous past. He once nearly killed a guy in a bar fight, but that was a long time ago. And according to one innkeeper's wife, who says it with a chuckle, "Ramon has screwed every woman in Elk—with the exception of me of course." Ramon denies this. "It may sound good, but it isn't true." He says he has gone long periods in Elk without a woman.

In fact he claims Elk is a great place for celibacy, as he says there are not that many attractive women. I suggest he keep that opinion to himself, as Elk women, if not attractive, are certainly tough.

I mention that I'm surprised that Karen (not her real name), a woman who used to live in town, is now hooked up with Todd (not his real name). "Well, good luck to him," says Ramon. "When I was with her all she would do is cuddle in bed."

"You mean she was frigid?" I ask.

"Yes," says Ramon, "an ice box."

He said they talked about it but things never changed. I was a bit surprised that Ramon had been with Karen; it just had not occurred to me. But his admission filled me in on something I had always wondered about. As it is, Karen is one of the more attractive women in Elk, and at one point I had had a slight interest in her myself. But I had gotten absolutely nowhere with her. What I mean is that I could not seem to spark the least bit of interest in her. She was available, she would have a conversation with you, but she was absolutely passionless unless you were talking about fears or anxieties. That is the one spark, in fact, that I had been able to raise in her; and that had occurred in a conversation about her children and anxiety about their safety. Beyond that our conversations went nowhere. I can even remember standing around at dances with her, asking her to dance, and her saying she was too tired or her back hurt. Now under other circumstances this could be a way of telling a guy to get lost. But with Karen I don't think it was; I think she would have said yes if she had not felt tired or her back didn't hurt. Now keep in mind that she was sexy-looking and attractive, so the whole thing just did not make a lot of sense.

Apparently cuddling did not prove satisfying to Ramon, so his affair with Karen was brief—so brief in fact that no one in Elk, where almost everything gets noticed, noticed. The flame ignited, at least for Ramon, then the flame sputtered out. For Karen her emotional temperature rose a few degrees, some ice perhaps melting, then it fell the same few degrees.

"Well, it's not easy to get it right, is it Ramon?" I say. He agrees. The lover and old brawler has seen his share of trouble.

I did not get around to asking his current status. The last time we talked he had gotten back together with a previous girlfriend, but I think that was not working out according to the "woman of the ranch," as we call the owner. The woman of the ranch knows everything. It is not enough if you own a ranch to know only the property lines, the number of cattle ... You need to know to the manners and the moods of the people who live and there and live near by.

I ask Ramon if he wants a shot of Whiskey. I have a bottle of Woodford Reserve. He says he is off booze.

"It's better that way," he says. "It just makes me crazy."

At once point, the court had ordered him to not drink. But that was a long time ago. It was after his fight. It is too bad to see Ramon have to "lock up the little crazy man" inside of him, as he puts it, but he says it is better not to "feed the little guy." I have a feeling that the "little guy" will be out soon. He is no longer violent, just moonstruck and romantic.

"Tea?" I ask.

"Next time. I gotta get going now."

Actually Ramon was doing quite well without booze. His eyes were clear and, as almost always, he spoke with amusement and animation.

He

went out in the dark, got hay from the barn, and spread it in two piles in

the meadow for the mules. Then he took off on his motorcycle. The mules were

eager for this treat that he brought them every night. I could hear the shuffling

of hooves and the occasional snorting of one or the other as they munched

hay in the meadow.

He

went out in the dark, got hay from the barn, and spread it in two piles in

the meadow for the mules. Then he took off on his motorcycle. The mules were

eager for this treat that he brought them every night. I could hear the shuffling

of hooves and the occasional snorting of one or the other as they munched

hay in the meadow.

The night was cold and I was still waiting for spring. I poured myself a shot and thought about life in the city. Now, in the woods, I could picture the naked girls dancing on the stage at the Hungry i. And I thought of Captain Morgan and spiced rum and Sage getting into graduate school, if that's what she wanted. I thought about Sunday and her parents back then when they gave their kids those lovely names. It was quiet out in the woods and there were lots of nice things to think about. The wind had stopped and I could almost say I felt happy.

Come, my love, let us go into the fields, let us see if the vines are blossoming, if the pomegranate trees are in flower. We will spend the night in the villages, and in the early morning we will go into the vineyards.

Home | City Notes | Restaurant Guide | Galleries | Site Map | Search | Contact